What is Storytelling?

Storytelling is a key aspect of narrative psychology, a branch of psychology that focuses on how people use stories to make sense of their lives. According to this approach, individuals shape their experiences, identity, and worldview through stories. Rather than focusing on isolated facts or events, narrative psychology examines how all our experiences are woven into a narrative that gives direction to life, whether on an individual level or across an entire society.

In this theory, we are constantly constructing our identity by viewing ourselves as the protagonist of an ongoing story. The experiences we have, the challenges we overcome, and the choices we make are all placed within a coherent narrative. This process not only helps us organise our lives but also enables us to cope with challenges and understand our personal growth.

Narrative psychology emphasises that culturally speaking humans have nothing but stories. We interpret and reinterpret our experiences, not through objective facts but by fitting them into a meaningful narrative. Thus, storytelling is essential to human development and identity. Skilled storytellers, such as writers, filmmakers, musicians, politicians, leaders, and influencers, can deeply influence the development of individuals, groups, and society. For this reason, understanding the guiding principles of storytelling and weighing the impact of stories is crucial.

Storytelling: an art and a skill

Storytelling is both an art and a skill. The art of storytelling lies in the ability to create stories that resonate with people, requiring creativity, empathy, and the ability to evoke emotions in the audience. Great stories do not just speak to the mind; they touch the heart. They have the power to elevate the human experience and connect us to something greater than ourselves.

The skill of storytelling involves understanding the structure of good stories. Many stories follow a familiar pattern that, while often applied unconsciously, is deeply ingrained in the human psyche. Storytellers are aware of the principles of story structure, which helps them make stories engaging and comprehensible, aligning with the way we experience the world. One of the most famous theories about this universal structure comes from mythologist Joseph Campbell.

Joseph Campbell, the Monomyth and modern storytelling

Joseph Campbell was an American mythologist best known for his concept of the monomyth, or the Hero’s Journey, outlined in his book The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949). Campbell discovered that many myths and stories from different cultures share striking similarities. He observed that these stories often follow the same narrative structure, which he called the Hero’s Journey. This structure consists of several stages in which a person receives a call to adventure, embarks on a journey, faces trials, endures a crisis, and eventually returns transformed as a hero.

Campbell’s theory was based on the idea that all stories ultimately represent human experience and development. The Hero’s Journey reflects the inner and outer challenges we encounter in our own lives. By casting these challenges into the form of stories, we give meaning to our experiences. Campbell’s work has had a profound impact on modern storytelling, from literature to film, with well-known examples like Star Wars following the Hero’s Journey.

Campbell’s original ideas on structure varied in the number of stages. One of his followers, Christopher Vogler, who worked for Disney Studios, developed a simplified version with twelve stages. This version was used in the design of The Lion King and many other Disney classics. The advantage of this simplification is that it can easily be mapped onto the twelve months of the calendar year.

Storytelling, the Circle of Life and the 12 months

Life moves in cycles, much like the sun, the seasons, and human life stages. These cycles have long been intertwined with the way stories are told. The “circle of life”, as described in various cultures, symbolises the ongoing cycle of birth, death, and rebirth. This cycle is closely linked to the course of the year, with each month and season representing a specific phase of life.

The twelve months of the year can be seen as metaphors for the different stages of a developmental journey. Stories often reflect these 12-month cycles, following the natural rhythms of growth, decay, and rebirth. This pattern can be observed in the Hero’s Journey, where the hero endures dark times (winter) but ultimately returns to the light (spring).

The Hero’s Journey and the sun

The Hero’s Journey, as described by Campbell and Vogler, can be viewed as a reflection of the sun’s path: rising, shining, sinking below the horizon, and rising again. This sequence of ascent, peak, descent, absence, and return occurs not only daily (day and night) but also yearly, as the sun reaches its lowest point at the winter solstice and then begins to rise again towards spring and summer.

This solar cycle symbolises death and resurrection, themes common in many mythical stories. The hero must ‘die’ (literally or symbolically) in order to be cleansed and reborn. This transformation, often occurring after a deep crisis, is at the heart of many powerful stories and represents humanity’s struggle to return stronger and wiser after hardship. These kinds of stories are shared repeatedly to provide hope and encouragement for transformation.

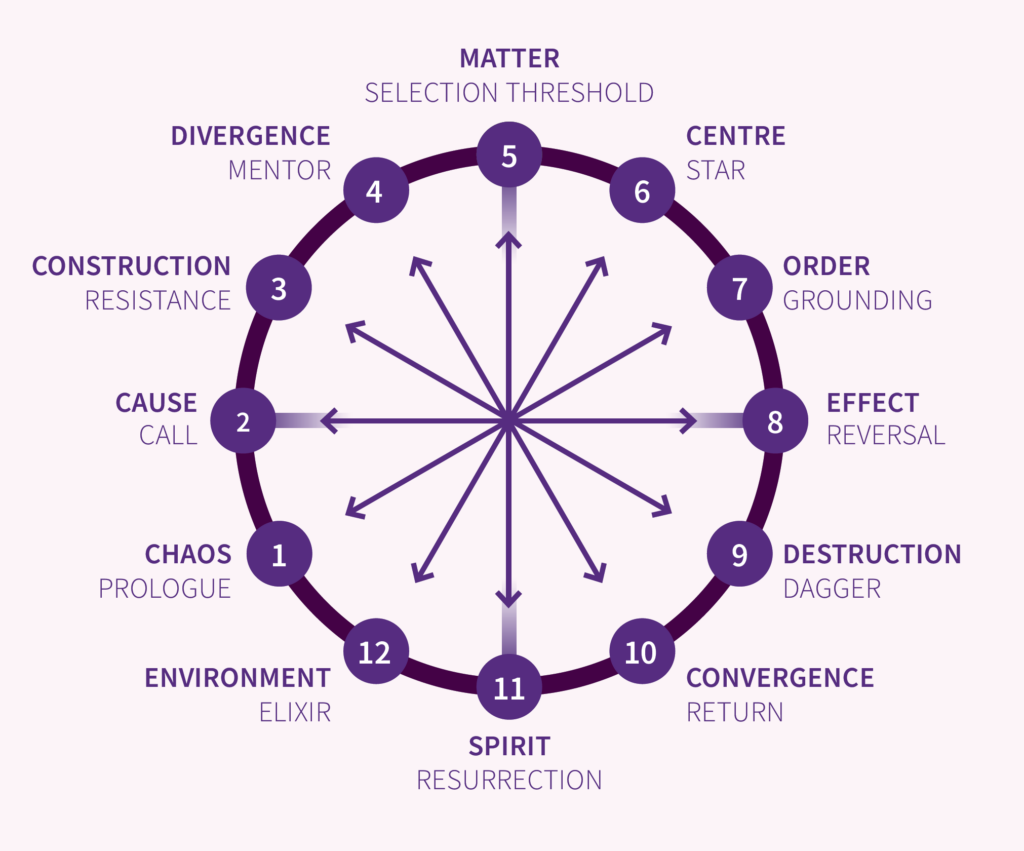

The story structure in the Double Healix framework

An effective story structure can be seen as a reflection of the twelve months of the year. Each of these months not only represents a specific phase in the hero’s journey but also a distinct quality that can be developed during that phase. These phases don’t necessarily follow one another in sequence but can also be used as components of a story to give it depth and meaning.

The Double Healix framework, based on the mythical Hero’s Journey, outlines the narrative structure of a developmental path through twelve phases. The Double Healix model then spans seven levels of human development:

– Childhood development phases and basic needs that manifest throughout life

– Adolescence phases and personality types/defence mechanisms

– Young adulthood and personal leadership competencies

– Mid-adulthood and phases in teamwork and collaboration

– Mature adulthood and phases in organisational development

– Early old age (healthy ageing) and twelve stages of societal formation

– Mature old age (healthy dying) and twelve areas of mystical experience.

Before delving deeper into these recurring phases of development, we must first take a slight detour to explore the thematic tensions inherent in storytelling..

The Double Healix framework for Synchronous storytelling: the tension fields

Every story contains thematic elements that pose fundamental questions about the human condition. Each phase highlights a particular theme, and every theme contains a tension that is explored during the story. Before outlining the sequential structure of the universal story, we must first examine the underlying themes that always manifest through these tensions.

The tension between Chaos and Order

Forrest Gump in Forrest Gump (1994): “I don’t know if Momma was right or if it’s Lieutenant Dan. I don’t know if we each have a destiny, or if we’re all just floating around accidental-like on a breeze, but I think maybe it’s both. Maybe both is happening at the same time.”

Every story grapples with the question of whether destiny exists or if life is mainly governed by random, meaningless events. This tension plays out in how much control the protagonist can exert over the course of events. Does your main character have an intuition about what will happen? Do you weave predictive symbols or dreams into the narrative? Or do you have your protagonist experience a series of disjointed events in an indifferent universe?

The Chaos-Order tension is important not just in the content but also in the story’s structure. As a storyteller, you must decide how much form to impose. Like a good piece of music, a well-told story incorporates at least a few recurring patterns to offer the reader, listener, or viewer some stability. However, an overly rigid structure can feel contrived.

A key element in any story is the ‘beat’. In storytelling theory, beats refer to the smallest units of action or emotional change within a narrative. A beat marks a specific moment that influences the story’s progress or changes the dynamics between characters. It serves as a building block of the plot, ensuring a smooth progression. Characteristics of beats include:

– Action or emotional change: A beat can be a physical event (like a character’s action) or an internal emotional shift.

– Small story units: Beats form the foundation for larger narrative elements, such as scenes and sequences, and give the story structure, rhythm, and pace.

– Change: Each beat introduces a small shift, such as new information, a decision, or a conflict, moving the story forward. Too few beats make the story dull, while too many can make it feel disjointed.

There are different types of beats, such as:

– Action beats: Physical events or actions by characters that propel the story.

– Reaction beats: Emotional responses or decisions following an action that influence the story’s progression.

– Dramatic beats: Moments of tension, conflict, or revelation that heighten emotional stakes.

Together, beats help keep a story dynamic and engaging, providing the necessary motion and change at both the plot and character development levels.

The tension between Cause and Effect

In The Matrix (1999), Morpheus says: “Everything begins with choice.”

Another important tension in storytelling is understanding who takes the initiative and what the consequences of those actions are. This aligns naturally with the earlier tension between Chaos and Order. We are not only concerned with how much of life is ordered, but also whether our actions have consequences, and over what time frame these consequences unfold. A classic variation involves the protagonist being struck by fate, only to gradually realise that this fate is tied to their own purpose in life. The protagonist evolves from a helpless victim to a co-creator, responsible for their own narrative.

A compelling application of the Cause-Effect tension is the delayed consequence. The protagonist may take an action early in the story that has unexpected repercussions later on. This ties into the important question of whether humans are subject to the laws of Karma or a punishing and rewarding god. Delayed consequences allow for a sense of freedom. If we were immediately rewarded or punished for our decisions, we would be too conditioned to make free choices.

In The Matrix, the story constantly revolves around whether Neo, the protagonist, is free to act or merely following a pre-programmed path. Once again, the balance between Cause and Effect is crucial. Too much ‘Cause’ suggests a kind of omnipotence in the protagonist, while too much ‘Effect’ reduces the protagonist to a pawn of fate.

The tension between Construction and Destruction

Dom Cobb in Inception (2010): “An idea is like a virus. Resilient. Highly contagious. The smallest seed of an idea can grow. It can grow to define, or destroy you.”

The tension between Construction and Destruction addresses the degree to which the protagonist suffers. A light-hearted family story may limit the suffering to something minor, like a lost dog that gets adopted, whereas a film noir highlights the weight (or darkness) of existence. This choice depends on the intended audience and their emotional resilience. Often, a strong story includes a painful low point, followed by catharsis and redemption, giving the audience a sense of relief. For some cultures, however, such a “Hollywood ending” is less convincing, and stories from Russian and Chinese traditions may end in a more sombre or minor key.

This contrast between major and minor endings speaks volumes about the nature or the storyteller’s choice. With an uplifting tone, you can narrate even the most painful events without overwhelming the audience, whereas a darker tone can make even a small incident unbearable.

A third way this theme appears is in the character development of the protagonist. A character may start off cynical (Destructive) and slowly grow into hope and harmony (Constructive), as seen in Groundhog Day. This film follows a cynical reporter who relives the same day repeatedly until he overcomes his cynicism and underlying narcissistic depression. Alternatively, the character arc can be reversed, with the protagonist starting in harmony (Constructive) and ending battered but enlightened (Destructive). In his influential book Story: Substance, Structure, Style, and the Principles of Screenwriting, Robert McKee describes the tension between Denial (an unconscious refusal to face reality, maintaining a Constructive harmony) in the early stages of a story, and Negation (a conscious lie) at the end. The protagonist, through a dark, deliberate action, loses the last illusion about their true self (Destructive).

The tension between Divergence and Convergence

The Ancient One in Doctor Strange (2016): “We never lose our demons, Mordo. We only learn to live above them.”

The tension between Divergence and Convergence dictates how much humour (Divergence) versus seriousness (Convergence) is present in a story. Even in the gravest of tales, humour is essential for providing comic relief, just as comedies often contain sharp insights. Indeed, the essence of comedy often lies in addressing serious subjects by exaggerating them.

When crafting the structure of a narrative, as a storyteller, you must decide how many storylines you will introduce (Divergence) and whether, and how, you will weave them together as the plot progresses (Convergence).

Another dimension of this tension lies in the complexity and ambiguity of the characters. You may choose to create complex, multifaceted characters (Divergence) or more straightforward ones (Convergence). A harmonious balance can be achieved by giving characters a ‘character arc’ that resolves some of their initial ambivalences. Alternatively, you can reverse this, starting with simple characters and revealing their complexities as the story unfolds.

A fruitful use of this tension is seen when supporting-characters in the story express various perspectives that the protagonist shares. This is a common technique in classic dramas like Hamlet, as well as in comedies. An extreme example of this is Mr. Robot, where the protagonist’s mind is portrayed as housing multiple voices. A comedic variant can be found in Scrubs, where the protagonist is visited by both angels and demons. A semi-comic take on this is The United States of Tara, where the protagonist suffers from dissociative identity disorder.

One final, but crucial, use of this tension is when the protagonist wears a mask (Divergence), only to remove it by the end of the story and stand in their own truth (Convergence). This same principle can be seen in a chase sequence, where all plotlines eventually converge towards the story’s conclusion.

The tension between Matter and Spirit

Valerie’s letter in V for Vendetta (2005): “Our integrity sells for so little, but it’s all we really have. It is the very last inch of us… but within that inch, we are free.”

The tension between Matter and Spirit forms a crucial axis in storytelling. Matter represents the concrete, rational actions and measurable, tangible events in a story. Spirit, on the other hand, embodies the emotional, moral, and spiritual values we assign to these events. How much meaning does a storyteller wish to imbue within the narrative? How many underlying messages should be conveyed? Or does the story remain more of a neutral, documentary-like observation?

In the structure of a story, this tension often plays out between the preservation of the body (prudence) and the preservation of the soul (justice). In many hero tales, the protagonist initially fights for physical survival, but by the climax, they often make a sacrifice that endangers their body but saves their spirit. A well-known variant is the ruthless businessman or businesswoman who, by the end of the story, follows their conscience, as seen in the film Miss Sloane, which deals with the tension between ambition and ethics.

This tension also affects the overall atmosphere of the story. Is the setting grounded in the harsh, material world (business, politics, crime), or does it dwell more in the realm of emotion (family, romance, mysticism)? It’s highly effective when crossovers are made between these domains, such as bringing elements of spirituality into a story set in the corporate world, and vice versa.

The tension between Centre and Surroundings

Tony Stark in Iron Man (2008): “I shouldn’t be alive… unless it was for a reason. I’m not crazy, Pepper. I just finally know what I have to do. And I know in my heart that it’s right.”

This sixth tension concerns where the narrative’s focus lies. It begins with the storytelling approach: In the principle of the Centre, the story is often told in the first person, with a focus on the protagonist’s inner thoughts and experiences. In contrast, with the principle of Surroundings, the protagonist is described through the perspectives of other characters, or the narrative may focus on the development of a group as a whole.

In Western narratives, the theme often revolves around a hero who starts off too self-centred, only to realise through trials and failures that a greater cause exists. This reflects a transformation from an individualistic culture to enlightened self-interest. In collectivist cultures, the reverse is more common: a protagonist who is too self-sacrificing gradually learns to stand up for themselves. This tension between Centre and Surroundings can also manifest on a personal level. For instance, in English Vinglish, a submissive housewife, who bakes cookies to sell, gradually realises her own worth and begins to gain recognition.

A thematic variation of this tension is seen in stories of egocentric kings or queens who, after a revelation, realise the need to care for others. This is often symbolised by the warm heart, serving as a metaphor for a centre that nourishes its surroundings.

The tension between Sequential and Synchronous storytelling: the seventh tension field

Louise Banks in Arrival (2016): “But now I’m not so sure I believe in beginnings and endings. There are days that define your story beyond your life. Like the day they arrived.”

We have now discussed six tension fields that have applications both in content and structure. The seventh tension field (referred to as “six plus one” because it is fundamentally different) deals with how the story handles time.

Sequential refers to a linear and chronological approach: the story starts at the beginning and events unfold in historical order. Synchronous, on the other hand, presents the story in a single moment, like in a painting or a photograph. There are also synchronous narrative styles where parallel stories are told, as seen in split-screen storytelling in films. A milder version of this technique involves rapid shifts between storylines, known as cross-cutting. There are also hybrid forms, such as starting the story at the end or incorporating frequent flashbacks.

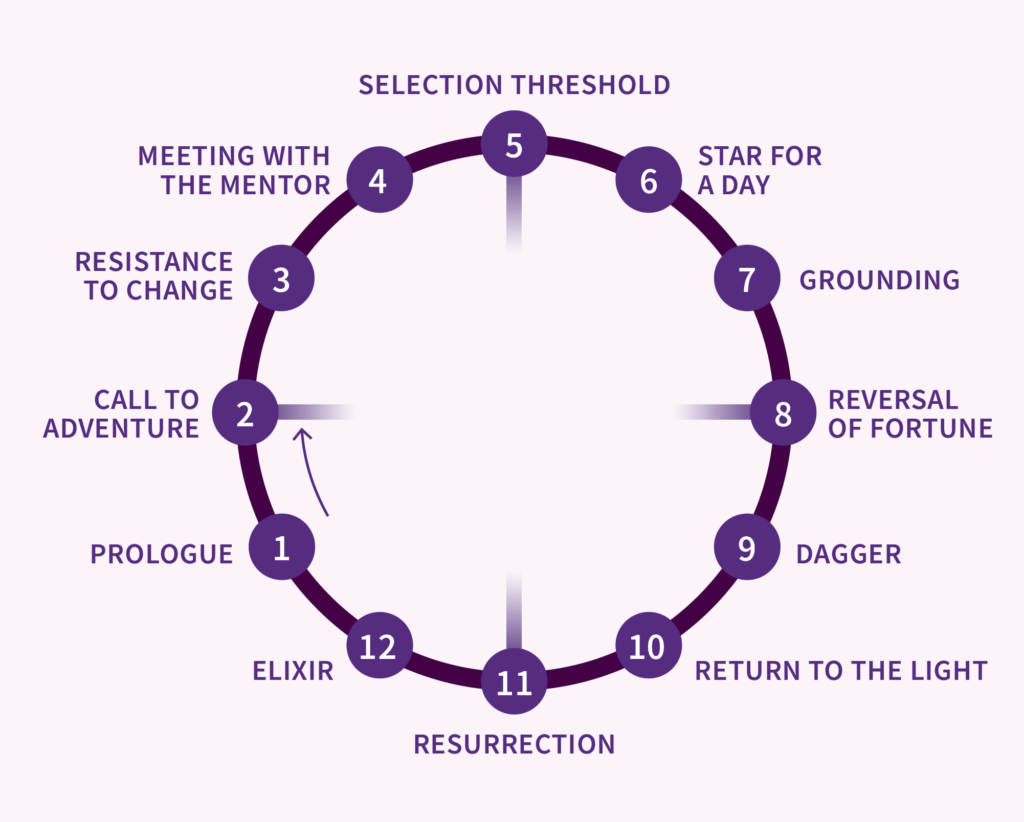

The Double Healix framework for sequential storytelling: the hero’s journey

We now return to the metaphor of the journey as a reflection of the yearly cycle and will discuss the 12 phases of the journey as they sequentially follow one another in the story. At each stage, we will briefly reference the underlying principles of the phase with corresponding imagery from astrology.

While the underlying principles influence all stages of the journey, they tend to be more dominant in certain phases than in others.

1. The Prologue (Pisces - Early spring)

The prologue is the stage where the story begins, often without a clear sense of direction. The subconscious plays a significant role, with an underlying feeling of restlessness and ambiguity. This phase symbolises the unconscious preparation for the adventure. The protagonist is unaware of the journey ahead, but an invisible shift towards change is already in motion.

The underlying principle is Chaos, from which everything is born and to which everything returns. Early spring can be seen as the seeds beneath the ground, quietly stirring.

The astrological symbol of Pisces is significant here, representing the chaotic multitude of fish swimming in schools, as well as the cyclic nature of life, like the salmon returning to its birthplace to spawn, lay eggs, die and return in the form of the offspring. The association with early spring evokes the image of new life lying dormant beneath the surface, much like an embryo in its fish-like stage of development.

2. The Call to Adventure (Aries - Spring equinox)

As the days grow longer and light gains strength, the protagonist feels a pull to embark on a journey.

The underlying principle is Cause, as the protagonist is challenged to take action and let go of the familiar and the safe.

The image of Aries is one of forceful birth, symbolising the sprouting of plants breaking through the earth’s crust.

3. Resistance to Change (Taurus - Green pastures)

Here, the protagonist resists the changes that lie ahead. Like the springtime preparing for growth, strength must be gathered to move forward.

The principle of Construction applies, as the protagonist gathers the willpower to persevere.

The image of Taurus represents the steadfast nature of the bull, capable of transforming stubborn grass into rich protein and muscle. Taurus evokes the image of green pastures, where the bull performs its transformative, chewing work.

4. Meeting with the Mentor (Gemini - Colourful wildflower fields)

At this stage, the protagonist encounters a mentor or guide who offers essential knowledge and tools. The protagonist gains new perspectives on reality and themselves, which increases their willingness to embark on the adventure. In some cases, this shift occurs through insights the protagonist discovers on their own.

The underlying principle is Divergence, as the hero explores choices and new insights.

The image of Gemini is that of versatility, reflecting oneself in another. In the yearly cycle, it is the rich colour display of various blossoms.

5. The Selection Threshold (Cancer - Summer solstice)

The protagonist reaches a critical phase of testing, where they must prove themselves worthy to proceed. This is the moment of trial before entering the “special world.”

The underlying principle is Matter, where the tangible results of earlier efforts start to show.

The image of Cancer evokes several associations. Firstly, Cancer has a tough exterior but a vulnerable interior, much like Darth Vader in Star Wars. Additionally, Cancer is a hierarchical and materialistic creature, equipped with various tools, symbolised by its different claws. The association with early summer is the red hue of a sunburnt skin, “red as a lobster.”

6. Star of the Day (Leo - High summer)

The protagonist, believing the worst is behind them, starts to revel in success. Summer is at its peak, and the protagonist feels invincible. However, this is often the phase of overconfidence.

The principle of Centre is key here: the protagonist is at the centre of attention but still vulnerable to mistakes.

The image of Leo reflects the loud roar of the lion, the symbol of the king of beasts. The lion’s mane often represents the sun’s rays, and the association with mid-summer evokes a sense of feeling like a king, “ruling the summer.”

7. Grounding (Virgo - Harvest time)

As summer draws to a close, the protagonist begins to confront reality. Preparations for the second half of the journey—through the underworld of night and winter—begin.

The underlying principle here is Order, where the chaos of the beginning must now be tamed.

The image of Virgo can be understood in terms of a woman’s careful choice of a suitable partner for fertilisation. This stage is sometimes referred to as the ‘Approach of the Inmost Cave’ or ‘Meeting the Goddess’ in the hero’s journey. But for everyone, the conscious application of intuition, reliability, and organised attentiveness is essential. Virgo’s attribute, the ripe ear of corn, links to the season, posing the crucial question: when and how should the harvest be reaped?

8. The Reversal (Libra - Autumn equinox)

The protagonist faces the consequences of earlier actions, with fortunes seemingly shifting beyond their control.

The underlying principle is Consequence. The protagonist begins to realise that choices and actions have unavoidable repercussions. This marks a significant turning point in the story, where the protagonist must restore balance.

The image of Libra refers to the only inanimate archetype of the twelve images, a passive instrument that works best when exerting no influence over the weighing process. It symbolises being moved rather than moving oneself. The connection to the autumn equinox is evident—days grow shorter than nights, and though expected, we’re always caught off guard by the creeping cold and sudden autumn storms. Rilke’s poem “Herbsttag” expresses this transitional mood. Superficially, this shift may be seen as a change in weather, but deeper, it signals a change in the tone of the story, which now takes a grimmer turn.

9. The Dagger (Scorpio - Slaughter month)

This is the story’s darkest point. The protagonist faces loss, betrayal, or a deep crisis and must confront the painful realities of what went wrong.

The underlying principle of Destruction comes to the fore, as the hero grapples with the darker sides of human experience. This is the ‘dark night of the soul’ phase.

The image of Scorpio stands for sharpness, secrecy, and death. The saying “Venenum est in cauda” (the poison is in the tail) highlights how the painful twist often arrives at the end of an interaction. In the year’s cycle, it’s the slaughter month of November, when well-fed animals are butchered to provide sustenance for the dark months ahead. Scorpio, therefore, carries both negative (destruction) and positive (insight and richness) connotations.

10. Return to the Light (Sagittarius - Dark winter days)

Despite the crisis, the protagonist begins to see a glimmer of hope. There’s a renewed sense of focus and direction, often heralded by the ‘return of the mentor.’ The protagonist recalls the mentor’s key lesson and uses it to emerge from the crisis. Often, this leads to the final chase that will culminate in the story’s climax.

The underlying principle is Convergence: the protagonist makes choices that lead toward resolution and a way out of the darkness.

The image of Sagittarius is fitting here, symbolising the aim and drive needed to rise from the underworld. In the seasonal cycle, this corresponds to the dark days before Christmas, where the lighting of a single candle in a dark room represents hope that the light will return.

11. Death and Resurrection (Capricorn - Winter solstice)

The protagonist faces the ultimate test. This is the moment of death and resurrection, where the protagonist is transformed into a true hero. It’s the ultimate test of character—will the hero stand by their principles?

The underlying principle is Spirit, as the protagonist understands that the physical is subordinate to spiritual growth.

The image of Capricorn stands for enduring solitary heights. The goat’s climb up the mountain is symbolic of the winter solstice, the point where the sun appears to stand still and then begins its return. This stage is often associated with the hermit, a figure linked to introspection. As we reflect on the past year during the solstice, we also set intentions for the year ahead, undergoing a small rebirth ourselves.

12. Return with the Elixir (Aquarius - Refreshing new world)

The hero returns to the ordinary world, now enriched with wisdom and strength.

The underlying principle is Periphery: the hero shares their newfound knowledge with the community and becomes a servant of the greater good.

The image of Aquarius symbolises the act of giving. In ancient depictions, we see the vessel of the water bearer being filled by the same stream from which it pours, representing the fulfilling nature of helping others. This fits the end of the journey, where the fruits of the adventure are shared with the world. At a literal level, this is often felt as the arrival of a fresh new world, such as when the first snow falls. It’s the moral of the story, and often the epilogue serves as a preparation for a new cycle. The storytelling never truly ends.

An example of a well told story

The below video tells a love story told by Aryana Rose. Can you find the 12 phases in her story?

Storytelling and Personal Development

Thus far, we have explored both the synchronous and sequential structure of storietelling. Understanding these structures goes beyond mere storytelling; the archetypal phases also help us to better comprehend our own life journey. We all go through universal periods of growth, crisis, and resurrection. Not just once, but through multiple cycles at various stages of maturity. By recognising these phases in stories, we can place our own lives into perspective, gaining greater insight into where we currently stand in our personal development: what path we have travelled, which phase we are in, and what might help us to take the next step in our journey.

Stories not only guide our thinking, but also serve as metaphors for the cyclical nature of life. Through telling and listening to stories, we learn the lessons embedded in these cycles. This way, we not only become better storytellers but wiser individuals. In the many adventures of life, storytelling enables us to better understand both ourselves and the world around us. Storytelling is not merely an art or a skill; it is an essential tool for navigating life’s challenges and understanding the meaning of our experiences.

Multiple stories, conspiracy theories and empathy

It is important not to become fixated on a single story but to tell, listen to, and engage with multiple stories. This diversity of perspectives helps us to break free from narrow viewpoints and develop empathy for alternative interpretations. Whether they are mainstream stories, controversial narratives, old or new tales, or even so called conspiracy theories, almost all stories contain kernels of truth and are worth exploring and considering within the flow of perspectives. Each story contributes to a broader understanding of the world, offering fresh insights and challenging preconceived notions. By embracing this multiplicity, we can cultivate a deeper sense of connection with others, recognising that no single narrative can encompass the entirety of human experience. Engaging with multiple stories fosters intellectual growth, critical thinking and emotional resilience, allowing us to navigate life’s complexities with greater wisdom and understanding.

Learn how to tell captivating stories with the online course from Double Healix

The story structures we have discussed in this article are covered in depth, richly illustrated with a diversity of inspiring film examples in our MovieLearning course, Storytelling – Step by Step:

- With examples from many of the best feature films

- Created by top narrative psychologists and psychotherapists

- Includes numerous explanatory videos, analyses, tips, and exercises

- Over 100 scenes from films, documentaries, and series

- The course is highly valued by participants!

![[:nl]Double-Healix-Logo[:]](https://doublehealix.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/rsz_invoice_logo-e1591168417490.png)